Gasoline and Matches: A Lyndy Martinez Story, Part-2

Lake Arrowhead, CA 1990s

Lyndy Life Observation: Rochelle Bishop had one of those 30-inch-wide natural hairdos popular in the seventies. She loved her enormous hair, but admitted it had drawbacks. Certain cars were dreadful to ride in, due to the low roofline and showers were practically impossible. One evening strolling out of Cadillac’s night club a small bat collided with her head, becoming tangled in it. Neither she nor the bat were harmed in the end, but Rochelle said she resolved it was time for a trim. This wasn’t an unheard-of occurrence back then, just ask any lady who had a giant beehive.

Kyle’s new cabin stood proudly on a bluff, with towering vistas of Lake Arrowhead. She found it challenging to describe the setting to one who’d never visited, other than comparing it to a tranquil slice of the Pacific Northwest transported to Southern California, then placed atop a mountain over the smog. The mountains were dense with vegetation in those days, mainly Douglas fir, ponderosa pine and incense cedar.

The custom cabin became the first home Lyndy lived in with solid non-tile counter tops. The kitchen was a true marvel. Those granite counters were an anthracite color, with flecks of embedded rock crystals reflecting light. The floors were real oak, textured with knots and little sanded imperfections. There were exposed beam trusses supporting the ceiling, and a tall set of picture windows with logs framing the lake.

One could get lost in that view, ever changing with the moods of the day. At daybreak or golden hour, the great room filled to the brim with inviting, natural light. Near sunset it could be distracting. It made you want to go out onto the deck and snap a picture, then rest your arms on the railing, take a breath and soak it in. You’d flick your shoes off, plop into a comfy chair and daydream. Soon you’d forget about the lasagna in the oven or the rice on the stove until a burning smell, or the beeping smoke alarm would jerk you back to reality.

She ruined many a dinner this way.

The more time one spent in this tree-house like environs, the harder it would be to return to desert living. Mornings on the lake were cool and crisp. Afternoons were sunny and warm. Colorful boats were constantly zipping from one side to the other. Throw in the change in seasons, like fall colors with mist swirling amongst the pines and it felt like another state entirely; Montana maybe. With a home like this one didn’t really need a TV. She spent many enchanting hours on that deck.

Another quirk: with the right angle of view, on the southernmost portion one could spot a corner of Rita’s mansion. You couldn’t see into Rita’s house per se, just a small piece of rock work. Enough to know it was there.

The name of Kyle’s cabin was Fall River, stenciled into a sign which hung by the door. Therein, another first. No one she grew up with lived in a house important enough to have a name. They didn’t give double-wide trailers names, nor did they give them to shitty stucco tract homes. Only custom homes had names. And Fall River was a very cool name, not because there were rivers anywhere near the cabin, but because of a place Kyle liked to fly fish.

On the lower level of the home paired with the bedrooms, the architects included a laundry nook containing both a washer and dryer. Such a welcome upgrade in convenience. Most places Lyndy lived had neither appliance, and she spent many weekend afternoons in the Amboy coin-op laundromat. But Fall River didn’t require a stack of quarters.

Course it wasn’t all an episode of Fantasy Island. With the house so new, it lacked furniture—two chairs were all they had for the table. No nightstand on either side of the bed. The clock radio rested on the floor. Worse, it also lacked any sort of baby proofing.

At 6 am, sun not yet rising on the lake, Lyndy kept busy hand-drilling small pilot holes for the plastic doo-hickey’s which restricted the lower cabinet doors from opening. Humming to music, she’d gotten into a groove. She worried most about the area under the sink, which she started on first, because here the cleaning chemicals were stored. Setting down the drill she began tightening the screws on these devices.

Using a towel to muffle the sound, she did her best not to make any unnecessary noise.

A few minutes later Lyndy was on hands and knees pushing the little plastic caps into the outlets when she heard Kyle’s footsteps on the stairs. She heard him yawn too. As his groggy head and shoulders poked above the landing, he spotted her.

Kyle was clutching the baby on his shoulder, supporting her bottom in the crook of his elbow. Mari was dressed in her favorite onesie.

“Couldn’t sleep again?” His voice sounded calm and sympathetic, even though she might’ve woken him.

“I got a few Z’s.” Lyndy sat up, still on her knees.

“What’s this?” he asked, poking at the open package on the island.

“It’s the baby proofing stuff I ordered. Remember?” Duh, she thought. What was wrong with dudes? Hadn’t he been through the process three prior times?

Kyle nodded as his expression morphed into “oh yeah.”

“In case you haven’t noticed, Mari will be crawling soon. She’s already reaching for things and putting random stuff in her mouth.”

Kyle gestured to the empty great room, near the windows. “Another thing. I was just thinking how we have no living room furniture.” He set Maribel down on the counter, in a seated position with her little legs dangling, which of course was unsafe. Lyndy quickly jumped up and scooped her off the edge.

“We need a sofa.” Reaching into the pantry cupboard, Kyle began pushing cans and bags of rice around.

“I made some coffee,” Lyndy remarked, holding the baby and walking a circle around the island.

Kyle sniffed. “Thanks.” When he turned around, he’d snagged the pancake batter mix and was holding the box on display with both hands. “How ‘bout I make breakfast?” He gestured to the sack of baby-proofing hardware, and the many lower cabinets still needing to be drilled. “After breakfast we’ll get the rest of those knocked out.”

Lyndy smiled, taking a seat with one of her legs folded under on a kitchen stool, while resting Mari’s bottom atop her thigh. Mari watched her father’s every move with attentive eyes as Lyndy gently bounced her up and down.

“I need to ask you something … and it’s … hard to picture,” Kyle stammered, in a tone balancing disappointment and understanding at the same time. “But did you call Rebecca Broom Hilda at the pool?”

Lyndy didn’t know how to answer, other than. “No. Of course I didn’t call her Broom Hilda. I mean … why? That’s preposterous!”

“So then, you didn’t call her a witch—any type of witch?”

“Technically no.”

By the letter of the law, I did not call her a witch. Lyndy held her tongue.

Stepping up to the commercial grade stove, Kyle twisted one of the big red knobs, making the natural gas his. He had his back turned as he slid his favorite cast iron pan into place, positioning it centrally over the burner. The hissing sound seemed to attract Maribel, making her even more interested. With a click of the igniter a ring of ten neat little cones of blue flame appeared, accompanied by a FWOOSH sound.

Maribel clapped her hands and said: “F-F-F-F-ire!”

Lyndy’s jaw dropped. Kyle whipped around, eyeing the baby in disbelief. He was holding a spatula which he pointed at Mari. Lyndy squeezed Mari’s sides, twisting and tilting the baby for a better look. She happened to have some spittle around her lips.

“Did she …?”

Lyndy’s wide-eyed expression was the same as Kyle’s.

Maribel glanced up first to her mother, then rotated back to face Kyle. Seeing her two parents so excited she knew she’d done something special. “Fwire!” she said again, louder and accompanied by a giggle. Then she stuck a finger in her nose. And that’s how the milestone of Maribel Ellis’s first word came to pass.

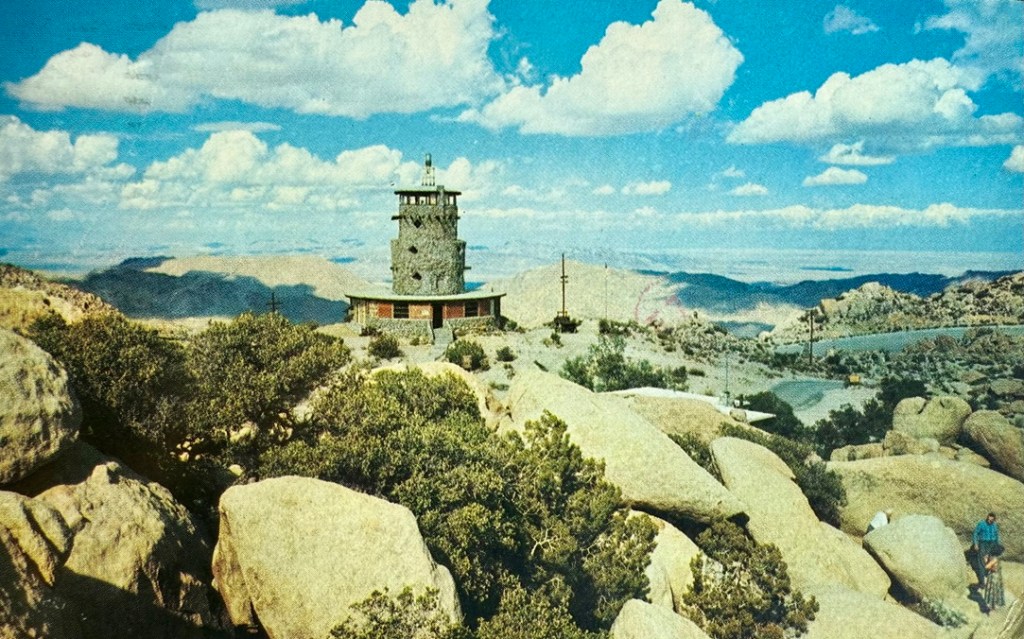

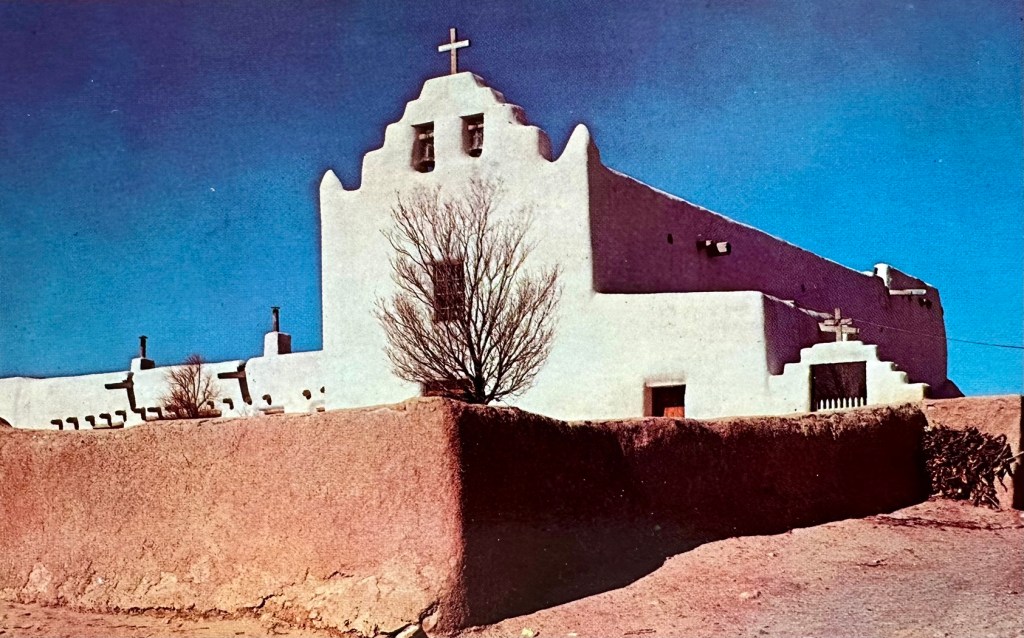

Wonder Valley, CA, 1990s

Lyndy Life Observation: Col. Rickman once remarked Swanson’s Hungry-Man TV dinners should change their slogan to: “official meal of the divorced American male”. Every time I think about that I laugh.

She threw down her shovel with enough force it dug in and stayed upright in place. Backsliding two paces, Debbie Kowalski allowed her drained body to collapse against the tailgate, resting her tailbone on the bumper. With a slow turning of her wrist, she ran her arm all across her forehead, shaking loose so much sweat it drizzled to the desiccated soil. She squinted her eyes at the bright July sun, feeling cramps in her stomach.

Weariness was taking hold. She needed a plan other than continuing to dig.

Debbie always took pride in self-reliance. Some of this stemmed from experiences with her Polish grandmother, a woman who not only survived a concentration camp, she literally worked as a slave sewing new uniforms for the Nazis. Suffice it to say, Grandma Kowalski was as tough a survivor as they come—a little piece of her spirit lived inside her granddaughter Debbie.

Debbie wore men’s pants, cowboy shirts and cowboy hats. Her high intellect and strong frame allowed her to do any job a guy could do. She went on adventures alone, fixed her own cars and generally solved any problem she came upon. She’d worked as a park ranger, a soil scientist for the USGS, a geo-chemist for a petroleum company and a cartographer. She’d hiked, driven and ridden horseback into some of the most remote spots in North America. She’d camped alone in grizzly country and trekked over sand dunes in Death Valley, carrying a fifty-pound pack.

Thus, it was disheartening to admit how hopelessly stuck in soft sand she was in the heart of her old stomping grounds. This was the Mojave Desert in summer, yet she hardly recognized the landmarks. The outlines of mountains were unfamiliar. The roads didn’t match the maps, and everything was powdery sand, burro brush and smoke trees. The only animals were distant vultures, circling hundreds of feet in the air. Gazing south, the horizon itself became distorted by heat convection.

Bending down, Debbie took another peek under the car. No change after shoveling. The Cherokee rested its four tons on the middle portion of both solid axles, colloquially called the pumpkins. Everything below, including two-thirds of the wheels were buried in the aforementioned fine sand. Like the car version of Ozymandias.

She cleared her throat. She had about a quart of Gatorade and a half gallon of drinking water. Two Mountain Dews. Should’ve brought more.

In literature they called the present condition a damsel in distress. Could one still be a damsel at forty-one? Maybe. Debbie checked herself in the driver’s side mirror. Her once carrot-colored hair from her Irish side, was turning a bit silvery. Her cute freckles peppered across her face, now looked suspiciously like age spots from too much time spent outdoors. Currently, this was covered up by the strawberry flush of heat. She was sweaty, probably smelled bad.

A younger version of herself had been a bit on the chubby side, but gradually she’d been losing some of the plumpness in her cheeks and also around the middle. With every year passing, Debbie found herself becoming the one thing she never thought she’d be—a slender woman. It was a strange turn of events.

“Stop wasting time. Need a plan.”

Debbie knew she was becoming disoriented. The symptoms of heat exhaustion were piling up. She’d tried any and everything she could think of to get the 1974 Jeep Cherokee unstuck, including unloading her gear to save weight. Still too much American steel and sheet metal. Even if she had an electric winch installed it wouldn’t have mattered. For miles around there was nothing sturdy enough to winch off. She possessed exactly one shovel, but anything she tried only seemed to make the problem worse.

Cupping her hand to shade her eyes, she tilted her chin back to study the sky. Not a single cloud. All these years, defying the odds. Being the greatest outdoors woman this side of … uh … Nelly Bly. Had her luck finally run out? The matter was settled. For the first time in months, she needed another person. As much as it stung her pride, a middle-age man with tools would be useful about now.

Debbie checked her watch, noting it was 2 in the afternoon. She staggered a few paces from the car, scrambling up the side of a berm iguana stye, to the nearest high point. With binoculars pressed to her face, she scanned along the horizon. Nothing manmade. Nothing moving.

Lyndy Martinez used to say: “anyone kooky enough to like it out here was automatically suspicious.” That was solid advice, under normal circumstances. But now, she was desperate.

The valley surrounding this spot was a western basin, an area in the rain shadow of multiple inland ranges with no outlet. Hardly any vegetation coated the soil. The mountains and hills were covered in exposed boulders, some of them a black or grayish color. Like a big Japanese rock garden. On summer days the sun roasted these stones, thus in each direction the horizon became distorted by the same rippling heat waves radiated by the rocks.

She tried again, scanning side-to-side across the mountains for anything man made. Could’ve been a mirage, but she stopped panning when she happened on a squarish cabin with two windows. The windows glinted in the harsh midday sun. Finally, a miner’s cabin! Had to be. She guesstimated the distance. Two miles perhaps? Though out here, distances could be deceiving, especially on a day like this.

Stop wasting time.

Jumping up, Debbie surfed down the slope with her boots. Slowing her speed and cushioning herself, she hugged on the car door excitedly. Next, she slipped the binoculars back in her Jeep. She left the windows down and her gear exposed, but crammed the keys in her shirt pocket. Without heavy equipment nobody would’ve been able to move that vehicle. A passer-by seemed unlikely out here. Besides, she planned to return to this point at the latest tomorrow morning.

She thought about writing a note. But what would it say? In case I don’t make it, here’s who I want to give my stuff too…

Hmmm. That felt too much like inviting the worst outcome.

Reaching in the cooler, Debbie popped the top and shot-gunned a cold mountain dew. She kept thinking about Lyndy’s warning not to trust someone who lived out here. Course, maybe the cabin was abandoned anyway. After shaking out every precious sugary drop, she tossed the empty can in the back. Then Debbie slapped her hat against her thigh, removing some of the dust.

Re-positioning her hat on her head, Debbie shouldered the one remaining jug of water and started off walking.

It took longer than anticipated, nearly two whole hours to hike from the jeep to the rolling hillside she’d seen from afar. When her tongue happened to touch along the edges of her lips, she tasted salt. But as she came nearer to her goal things were looking up. The shack dwelling appeared lived in. A handful of live plants, including a row of hollyhocks near a water tank were in bloom. Great news.

The other thing catching her attention was this hermit must be a bit of a collector. Her assumption at this point was a guy. Of course, anyone who lived out here was a hoarder by the classic definition. Out of necessity one had to hoard supplies to remain self-sufficient. She couldn’t fault them for that. But this person’s property was littered with aircraft parts—not barnstormer stuff but modern parts for jets. Expensive parts. They had pieces of an F14-Tomcat, including an engine. A few yards away stood the tail section of a DC10. On the other hand, they had D5 dozer parts too, including sprockets and rollers for the tracks. Hard stuff to move which must weigh tons.

“I don’t think UPS delivers out here,” she muttered.

Hopefully with any luck they were a mechanic type, with a running diesel truck or a flatbed to help get her out of here.

Zig-zagging her way uphill through the personal junkyard, she kept watch of the windows. She detected no motion in them, not even a flicker or glint of light. Nothing to indicate someone was watching from inside. Unfortunately, that meant surprising them.

No barking dog. Would she have to knock on the screen door?